Thinking of a new building for your non-profit, school, or social service? Read this first.

blog | Words Emma Whettingsteel | 04 Nov 2024

“We can’t do that, because this building won’t allow us to do it.”

Working in service design and innovation in social spaces, we sometimes come across this sentiment. Sometimes it’s a way of resisting change – but often they are right. Aspects of the built environment end up being a barrier to the services people need.

We see this most acutely in our work in homelessness and mental health housing, in schools, and in ‘one stop shops’. Spaces have huge impact. Not just in the way that clients and staff experience the service, but in the actual outcomes of the services. Buildings are not just about amenity or aesthetics. They can enable, or erode, the ways people engage with services.

The job of architecture is more than one of amenity or aesthetics. Rather, the built environment can enable, or erode, the way people engage with services. In schools, we hear that “space is the third teacher”, after teachers and families. This idea is true for all services, and so our buildings matter more than we think.

At Innovation Unit, we understand that, when we fully integrate service design and innovation practices with architectural design, we address social needs with greater creativity and efficiency.

Here’s how:

1. Understand that buildings have psychological impact

“A walk through a forest is invigorating and healing due to the constant interaction of all sense modalities.”

-Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses

Spatial cognition precedes language in the timeline of human evolution, and is deeply tied to our social and psychological sense-making.

Human bodies are machines for assessing danger: we all automatically respond to sensory information so that we can keep ourselves safe. In the spaces we work we know that small details are important for ensuring trauma-informed care. Physical surroundings affect this regulation. We become heightened or relaxed in response to external stimuli. In many settings, environmental stressors occur from the moment a service user walks through the door.

Physical spaces have a profound impact on social interactions and individual well-being. Buildings can be anxiety inducing, intimidating, and harsh. They can trigger negative memories of other spaces. Without anyone speaking a word, the environment of a service can send the message that you do not fit in, that you’re not in control, and you should not expect your needs to be cared for here. On the other hand, buildings can help create powerful emotions and stories for inhabitants, a sense of being in control, feeling connection, or hope. When we think about trauma-informed care, this needs to include treatment and design of physical space.

2. Communicate the building you need

Architectural designers traditionally focus on the physical structure, layout, and aesthetics of a space. But they can also set the emotional tone, relationship dynamics, and behavioural cues needed for a service model to work.

However, architects can only know what we, as service providers, communicate to them. We know how to tell them about duress alarms, or avoiding dead-ends in hallways for safety, or how many cooktops are needed in the kitchen. But do we have ways to tell them what the building needs to do – or not do – to help people heal?

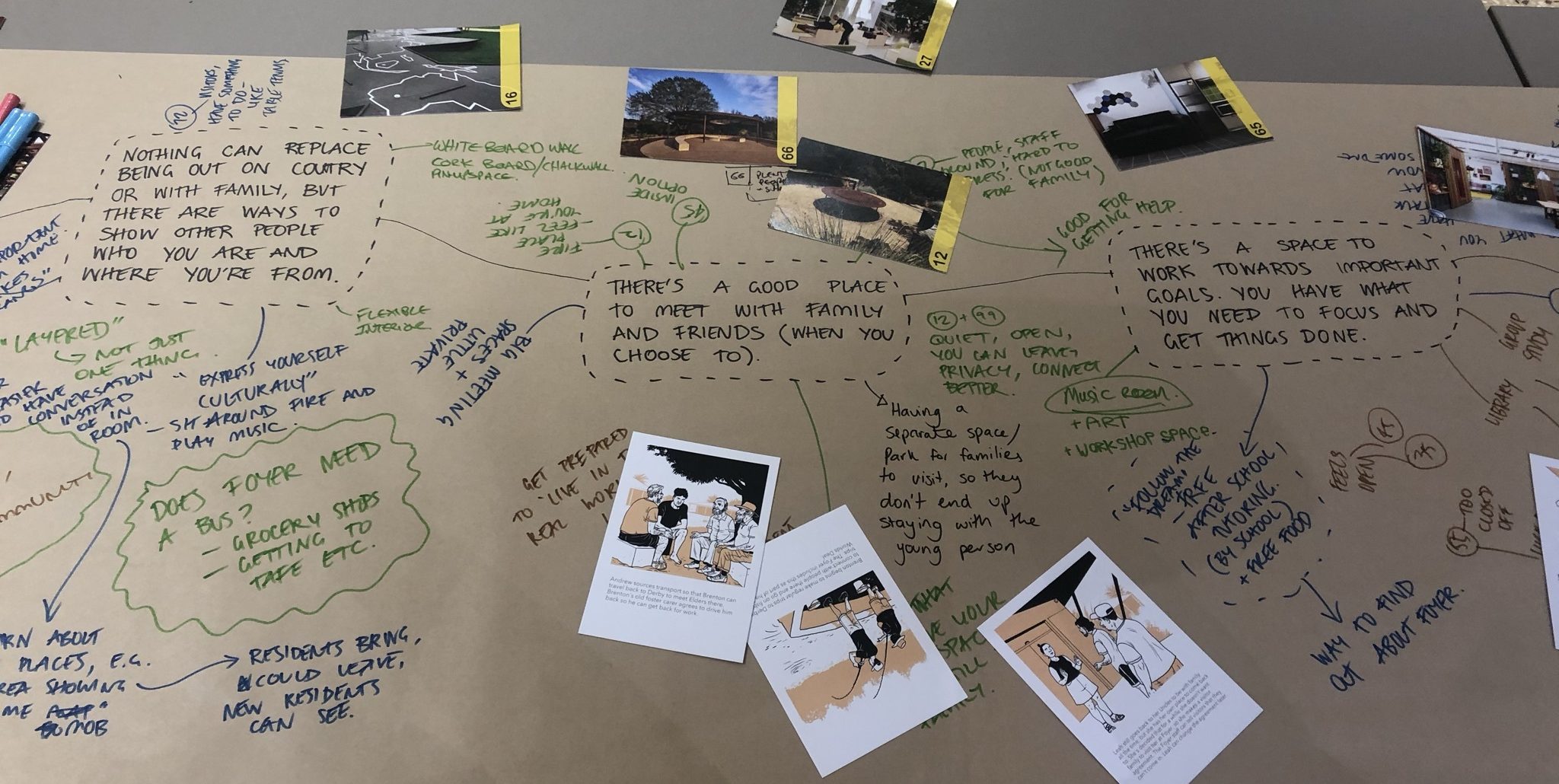

This is where service design tools are critical.

Service design is rooted in understanding and improving the overall experience of users, right down to the planning of how individual interactions and moments create an emotional journey. It has emerged from user-centred approaches to design and focuses on creating services that are responsive to the needs and feelings of the people who use them. Service design tools map how people will interact with the space, identify potential challenges or tensions, and propose solutions. These detailed insights allow architects to make thoughtful modifications that enhance the building’s functionality and social impact.

For example, in designing a community centre, service design can map out the various ways and ordering of how people will interact with the venue—such as attending workshops, meeting in groups, or accessing resources. This insight allows architects to create environments that not only serve their functional purpose but also to control and enhance the emotional and social experience of their users. By embedding service insights into the architectural design process, buildings become more than just a functional amenity, they are supportive tools for fostering positive interactions and outcomes.

3. Do it right, the first time.

Over and over again, we see the design of the service and the design of the building being approached separately. In practice, the service and the building are totally entwined and cannot be considered separate entities.

Planning service design and architectural design separately creates inefficiencies and additional costs. Often, misalignment between the intended services and the physical space results in costly adjustments or retrofitting down the line. Or worse, there are no funds to make adjustments, and staff attempt to work around the problem. Ultimately, staff engaged in service delivery are hampered and frustrated by the limits of their environment. They are unable to drive the impact they want.

To stop this cycle, we must integrate service design into the architectural planning process from the beginning. This approach ensures that the space is purpose-built to support its intended functions, and takes out the need for costly adjustments and inefficient work-arounds. Future frustrations can be anticipated and avoided in the design phase, and flexibility can be strategically designed in to allow for expected changes to needs over time. This extends the building’s usability and relevance.

4. Collaborate with your community

Service designers recognise the power of ‘co-design’. An effective service requires early and ongoing collaboration with the community and stakeholders who will use it. The same goes for the building. A co-designed built form is a powerful lever for ramping up ownership, belonging, functionality for end-users.

If this type of deep collaboration helps to ensure that human experience is shaping the service, and not the other way around. It also promotes a shared understanding of the project’s goals, which is crucial for achieving successful outcomes.

When done right, new buildings can act as rare, near permanent, flagship representations of collaboration and goodwill. People remember their involvement in them for long periods of time – driving past and thinking ‘I helped make that happen’. The capacity that humans have to attach to and care for places that they have social or symbolic involvement with is a powerful driver for service providers to harness.

5. Create ambition for the future

Many of our services have been forced to occupy buildings that are not fit for purpose – old apartment blocks turned into homelessness services, retail shop fronts into mental health supports, demountables into school rooms, old offices into service hubs. Service providers are accustomed to being resourceful and making the best of less-than-ideal spaces.

This necessity of making-do can become the enemy of more innovative and ambitious planning. When leaders commission new buildings, we notice a trap that many fall into, of planning an environment that supports the organisation as they are – not the one that they could be.

Before architectural concepts are designed, what if leaders rethought the service delivery itself. How could it change by listening deeply to our teams and the voices of lived experience? How might the service adapt in the future to changing contexts and environments? What front edge practices could be replicated, improved, and extended?

Early integration of service design and innovation practices helps articulate a clearer future vision for the project, and ensures that, in 5 (or 20) years time, you aren’t the person the next leaders whinge about (why the heck did they build it like that!).

This isn’t to say that existing buildings cannot be used ambitiously. It’s easy to miss the opportunity for adaptive and innovative use of existing spaces compared with the excitement and promise of a new build. They too provide an opportunity for better integration of service and architectural (or interior) design. Unlike new builds, which start with a blank slate, existing structures can of course come with their own set of challenges and constraints. However, there is always a chance to rethink and repurpose spaces in ways that align with contemporary social goals. Our observation is that we must resist the tempting notion that a new building will by default result in service innovation. An ambitious service is instead created through a rigorous and collaborative process of design between those with social and spatial expertise.

Regardless of the scale of the opportunity, building design and construction is a slow moving layer compared to service consultation and design. And the results last for a long time. The design of the built environment has a significant bearing on social outcomes, and yet the commissioning of architecture is frequently separated from the planning of service delivery. We need to challenge the idea that new buildings are inherently socially ambitious, or similarly, that existing and imperfect architecture is not compatible with innovative service goals.

If you are planning to commission a new building or renovation, how are you aligning the architecture with the social needs of your staff, users, and community? How will you communicate these complexities to architects and planners? What do you need from the building in 20 years? Service design might be the answer.