Three shifts we have to make in homelessness service design

blog | 04 Aug 2022

Putting home and healing at the centre of accommodation for those experiencing homelessness.

The most memorable conversation we had during our work on the Perth Common Ground development was with Andrea *not her real name*. We’d been hired by Gresley Abas architects to talk with people about what great housing should look like, and how the service delivery might interact. Andrea was a frequent, obviously much loved guest of one of the inner city drop in centres and was there for the art group.

Andrea held her arts practice closely, and as we discussed the kind of housing that had really ‘felt like home’ to her, she preceded to tell us about how she had managed to get through a little crawl space in a social housing property she once had and, using pallets and other found materials, built her own arts studio in the roof space. She laughed – “I don’t think they ever found it”.

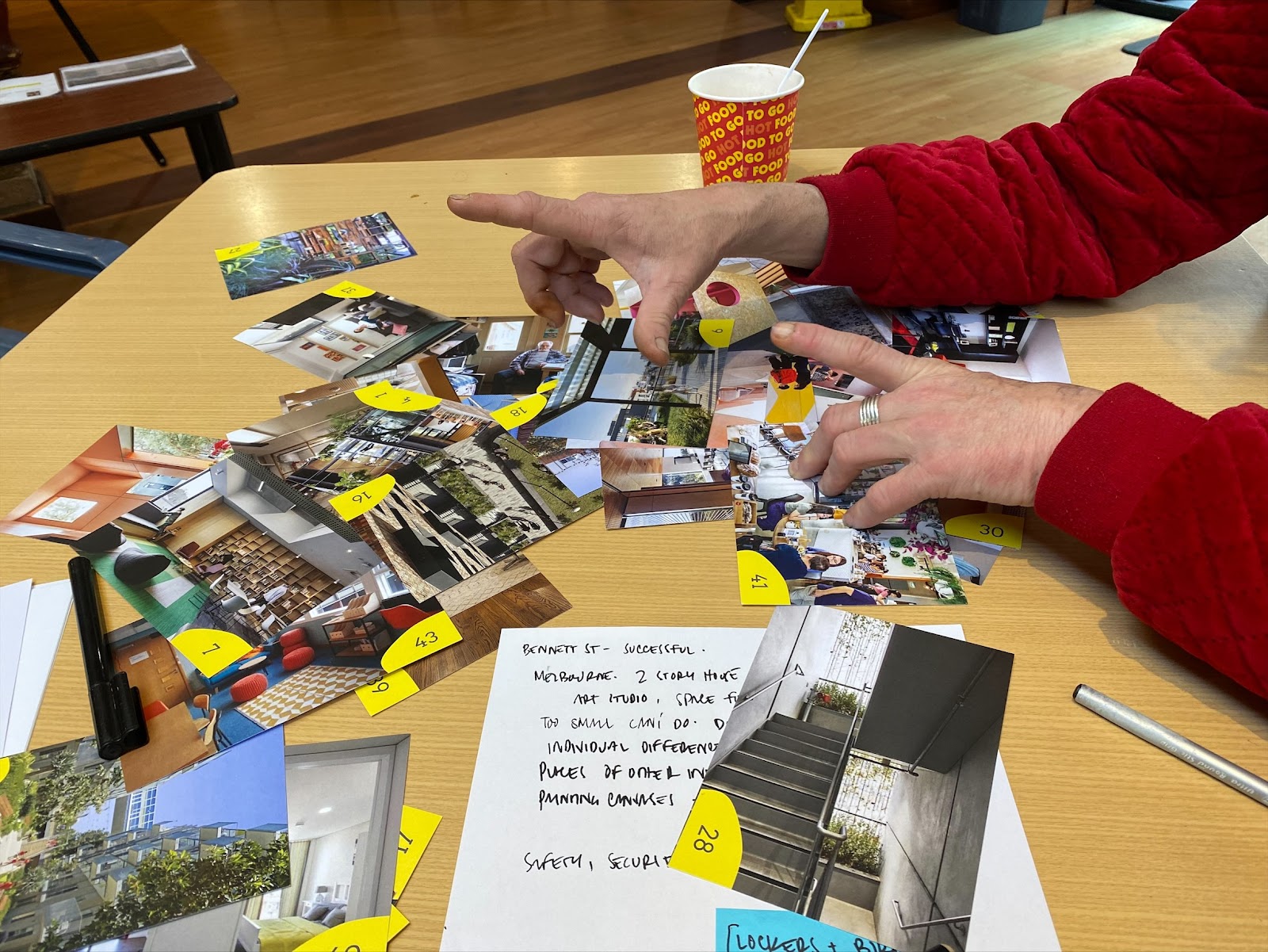

Andrea’s story resonated with us as she was one of many people we met who were finding work-arounds to create the spaces they needed to thrive. Work- arounds are often our best clues about what needs to change.

People are asking for a very different relationship with their accommodation services. They are struggling to find it in the business-as-usual approach of most existing service delivery. As we collected stories and opinions we found three shifts that we need to make if our service system is to deliver the kind of outcomes that are desperately needed:

- Space to focus on healing not just housing.

- Home comes first, services come second.

- Be an asset to the whole community.

Shift 1 – Space to focus on healing not just housing

“[That image of a garden space] looks inviting… Could have family around. My mum. Maybe my little brothers and my little sisters. Well, they’re big boys, but I still call them my little brother and my little sister. The plants and the people with their babies… I would love to have my babies as well to come over.”Lived experience participant

Too often ‘safety’ has been our driving design principle when we’ve developed spaces for people experiencing homelessness. People experiencing homelessness absolutely need physical safety as a baseline, especially after significant time in deeply unsafe spaces, but it needs to be the base expectation, not the driving force. We use safety as a reason to ban family and friends from visiting, and then wonder why people remain socially isolated.

Designing with higher expectations can support people to heal and grow. In the same way that adaptations have been made to facilitate independence for those with disabilities, could innovation in built form create housing that supports agency for people who have experienced homelessness? The simplified housing of “the Zero Flat” holds some of this promise. In particular people expressed a need for:

- Space to be out of the public eye, to have privacy. Much better sound proofing was emphasised to us, so that others couldn’t impact people with noise (and vice versa).

- Space for more than just living; for meaningful activities like gardening or art.

- Space for love and belonging; our service delivery must get much better at allowing space for friendships and family connections to flourish.

“One thing that cheaper buildings do, compared to wealthy buildings, is they cut back on insulation for noise and temperature. Those two things drive people f*****g mental.”Lived experience participant

Shift 2 – Home comes first, services come second

“If you build this building, and everyone drives past and says, ‘That’s where all the formerly homeless people live,’ then you failed.”Common Ground Service Provider

We suppose this is literally the point of ‘Housing First’ – that the primary thing we need to end homelessness is housing. In terms of accommodation spaces, as we spoke to providers, the projects that seemed to be thriving the most were those that had ensured that spaces felt primarily like homes, making their own service provision more subtle in the process. This included a rejection of institutional feeling spaces (even when these were modern, interesting ideas), making spaces for specialist service delivery less visible, and making sure that a sense of welcome was there the minute people walked through the door.

Because we’ve traditionally thought in service centred ways, we’ve instead put our front desks as the first thing people experience, and we’ve plastered our walls with pamphlets and posters. Our logos and sponsors names are front and centre. These things have served our services, but they’ve made our spaces not feel like home. Perhaps the most difficult part of the shift to a new way of doing homelessness delivery is that we have to decentre ourselves.

Shift 3 – Be an asset to the whole community

One of the real strengths of the Common Ground movement has been a focus on creating deeper connection and interaction with the community as a whole. This has also been a focus of the International Foyer movement. In both of these flagship models the principle is that services for people experiencing homelessness can be valuable community assets, rather than disruptions to good neighbourhoods.

This takes a mindset shift for service providers, as they seek to include the wider community, rather than defend themselves from hostile nimbyism. Can buildings create shared community spaces, like cafes, gardens or meeting rooms? What would happen if the art class at the shelter was for everyone in the neighbourhood? Can services that once only supported people experiencing homelessness be reframed as whole of community services?

None of this is easy.

Of course, none of this is easy. There are sound reasons that existing homelessness service delivery has had to focus on principles of safety for staff and residents, on a clear set of rules, on keeping apartment costs low, and on maintaining a highly specialised service delivery. We talk a good game on trauma-informed delivery, empowerment and agency, but unfortunately it feels like over time, the first lot have become our design principles, our normalised way of doing things. We have to be clear that people experiencing homelessness are asking for something very different.

What we also know is that every day we see the creativity of the service support system as it pulls together limited resources, leverages strong relationships, and shows resilience in the face of extreme pressures.

What happens if that creative capacity is harnessed to think differently about the spaces we create, and intentionally design places where people can thrive?

The team behind the development of the Perth based Common Ground projects have worked hard to learn from those providers who have used that creative capacity and the good news is that this approach is possible (though sometimes messy). “Feels Like Home” is the driving design principle for the Common Ground projects in Western Australia – can we achieve that kind of feeling more widely?

Concept image of Common Ground Perth – more here.

Contact Jethro Sercombe in our Perth office to talk about our approach to designing services with and for people experiencing homelessness.

The engagements for the design of Common Ground East Perth were conducted by Innovation Unit, Hatch Roberts Day, Gresley Abas and Kambarang Services for the Department of Communities.