Green energy, local jobs, warm homes

blog | Words Mike Rees | 12 Mar 2024

What can the past teach us about green energy and innovation in today’s political, financial and ecological climate?

The public debate on green energy and its affordability is never far from the headlines. The challenge of ‘doing more with less’ in the current climate of hard pressed public finances (and a hard pressed wider public) is acute.

To address this we look to a past innovation which brought together similar themes and assess how this might influence the way we approach today’s challenges. We return to the Welsh Valleys in the late 1980s and an economy standing on a cliff edge as a result of the mining and steel industry closures.

“This is my truth, tell me yours”ANEURIN BEVAN

It’s 1988. The MP for Islwyn is the Rt Hon Neil Kinnock (to become Baron Kinnock) and the leader of the Labour Party. He has just lost the 1987 election. His constituency has been hit by the closure of local pits putting thousands out of work. The proposed closure of Oakdale Colliery is an especially heavy blow.

Watching the devastation unfold around them four former pupils of Oakdale Comprehensive School – James Dean Bradfield, Nicky Wire, Sean Moore and Richey Edwards – are forming a band. They call it the Manic Street Preachers and their music will never stray too far from the impact of this time. In 1988 however, the so called ‘cool Cymru’ movement of the mid 90s would have seemed far removed from the immediate and pressing issue of an economy collapsing around its communities. The finest Welsh poet RS Thomas summed up the mood best:

“There is no present in Wales, And no future; There is only the past, Brittle with relics”RS THOMAS. WELSH LANDSCAPE

Islwyn’s Housing Energy Action Team (HEAT)

The official records of what came to be called the ‘Islwyn Housing Energy Action Team (HEAT)’ are hard to find. They are buried deep in the Gwent County Archives. So for this story, I rely on the memories of Mr Peter Docherty, Islwyn’s Chief Housing Officer at the time, some surviving newspaper clippings and my own memories as project administrator and council officer. So if there are any inaccuracies with dates and numbers, then please forgive me.

At that time Islwyn had around 6,500 council houses mostly built to post war or Parker Morris standards. Very few council houses had central heating, insulation or double glazing. Most had open coal fires and portable gas or paraffin for heating.

Winters can be brutal in the Welsh valleys. In the winter of 1986/7 a deep freeze and subsequent thaw caused 3,000 burst pipes among the 6,500 council houses leading to misery for families, huge damage and great cost. It had happened before but not on this scale. The only beneficiaries were the staff of the Council’s Direct Labour Organisation, with plenty of paid overtime making repairs.

Enter a young Scot by the name of Peter Docherty as the new Chief Housing Officer. The words ‘iconoclast’ and ‘maverick’ truly apply and underpinning this was (and still is) an unwavering commitment to provide ordinary people with good homes. Assessing the situation and doing the sums, Peter stated bluntly that no change was not an option and meeting the high cost of property damage every winter was unsustainable.

Peter won the support of local councillors and in particular, that of Cllr Barry Moore. Cllr Moore was also the constituency agent for Neil Kinnock (the two had been close friends since school days and Moore’s untimely death months before the 1992 election had a devastating effect on Kinnock). Docherty won his battle to raise the money to establish HEAT. Emerging from the agreement to press ahead was a clear expectation that the HEAT operation would offer employment to recently redundant miners. By Spring 1988 the scene was set.

From idea to implementation 1988-1991

The challenge was to insulate the loft, lag all the water tanks and pipes, and to draft-proof the windows and doors, in each of the 6,500 council houses. There would be 2 installation teams each with 11 men working in different parts of the Borough overseen by a small management, administrative and supervisory team.

The workforce, all of whom lived in the Borough, would also act as advocates in their own communities. This approach built trust with tenants. This allowed supervisors to explain to families the reasons for the work, its financial benefits to them and the council and keep to a minimum the number of houses where the insulation was stripped out and sold.

The work was completed in 3 years and provided jobs for about 40 men in total. Some left for other jobs to be swiftly replaced under an agreement with the local job centre. In the early days of HEAT, I worked out a way in which the Council could draw down national loft insulation grants from central government. This almost halved the cost per property while surpassing the national government’s stringent standards for insulation.

The biggest material cost was loft insulation. This was sourced from Rockwool who had , and still have, a local factory in nearby Bridgend. Doughnut economics is not new. Rockwool and other providers (Armaflex, Schlegel) were hands-on, providing training, expertise and encouragement.

We also introduced a new IT system to assess and record the condition of the housing stock. This helped to build an evidence base for future improvements such as double glazing and central heating. Introducing older ex-miners to their first ever office desktop computer is something that sticks in my memory.

Stories from the workforce were many and always human.

The teams often came across examples of real personal and family hardship in the homes they visited. They were able to refer people for support from the council social care, social security office, or voluntary groups. Kindness, solidarity and the long standing traditions of mining communities proved more difficult to make redundant.

The team, if memory serves me right, insulated the home on the Pantside estate of the family of Steve Strange, international pop star and leader of the New Romantic movement in the 1980s.

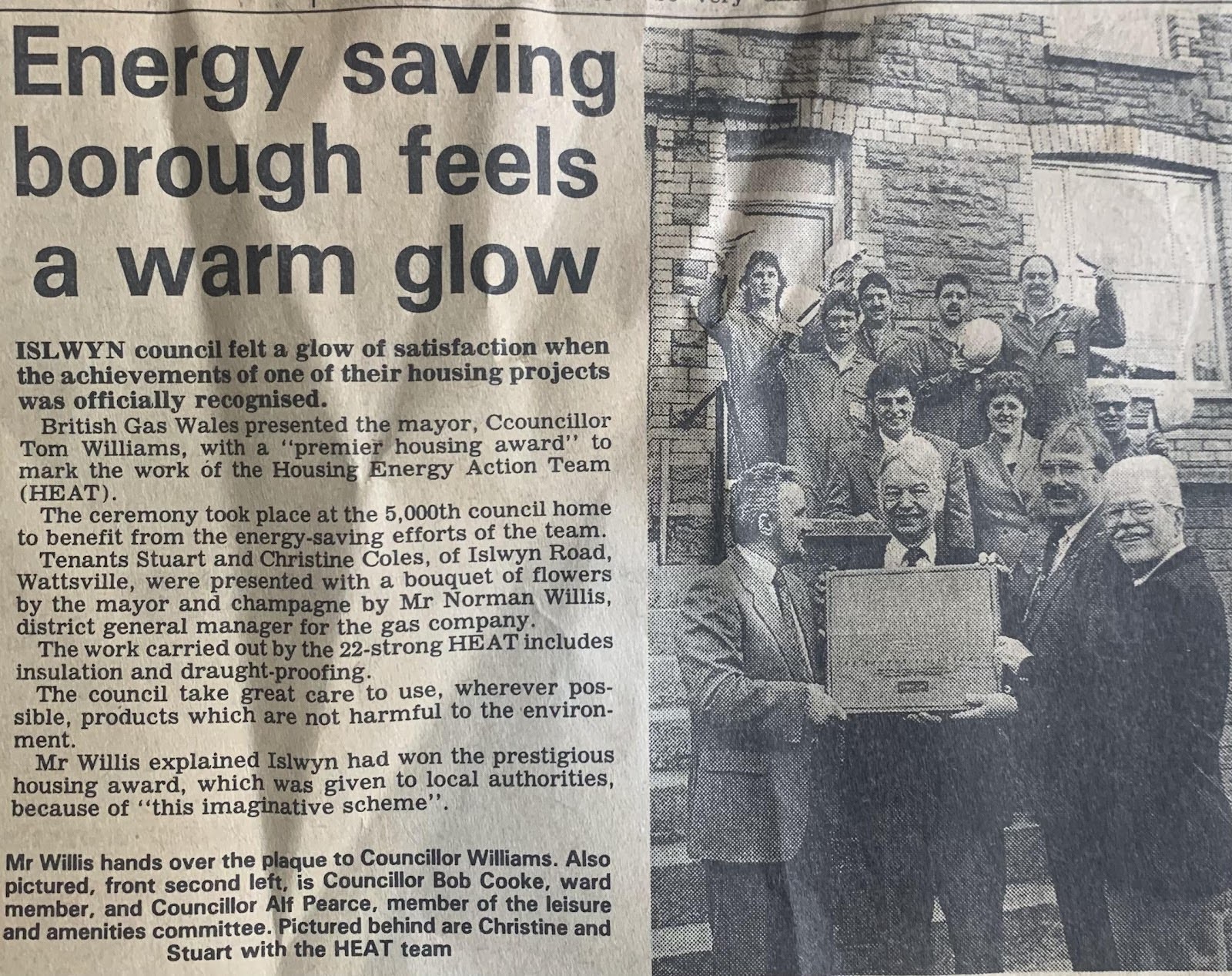

HEAT was gaining wider attention. It won a prestigious British Gas Wales award for this ‘imaginative scheme’ noting in 1990 that ‘ the council has chosen, wherever possible, products which are not harmful to the environment’.

Rockwool stated in May 1989:

“‘The loft insulation used meets not just today’s regulations but the proposed regulations soon to be laid before Parliament. We feel that Islwyn Council is tackling the issue of a cleaner future environment with great vision’.”South Wales Echo 18th May 1989

What had started as a local innovation and a gamble had quickly gathered enough evidence to demonstrate its value and many other local authorities were soon visiting to hear how it was being done.

Lessons for today

35 years later and green energy, net zero, the impact of climate change and the cost of heating our homes are rarely out of the news. We read and hear much about how jobs created through a revolution in green energy can bring back well paid employment to areas of the country in real need.

Indeed the Labour party is planning to put the UK at the head of a worldwide green industrial revolution (its Green Prosperity Plan), with a US-style, public-private investment scheme targeted at the most deprived regions.

But it’s important to ask ourselves whether we need a top down nationalised approach, or a more localised approach that creates space for innovations like HEAT. Could Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan actually encourage more localised innovation?

At Innovation Unit we argue strongly for more localised approaches to tackling climate change, that put communities in the driving seat, and create green energy and green jobs in places and communities that need them most. We have a long standing commitment to innovative responses to wicked issues and a track record of working locally to find the best solutions. Innovative policies dreamt up in Whitehall normally fail in places like Islywn.

Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan points out that we are investing five times less in green industries than Germany, and roughly half of France and the USA. It talks about growing our economy from the bottom up and the middle out. Its ambitions are to cut energy bills, create good jobs and provide climate leadership. It talks about regions having unique strengths – green steel, offshore wind, carbon capture & storage – and the need for the former industrial heartlands to lead the clean industrial revolution. This suggests that a national approach will have to be delivered locally with scope to invest in highly innovative local initiatives.

The localised impact of net zero will be contested. Often national top down schemes swallow costs at the top and the very local impact can be difficult to fully ascertain. Schemes such as the one in Islwyn, with local political support and benefits for residents and employees have such impact at the forefront of their ambition. So they go that extra mile and also generate other positive impacts as they go along.

At Innovation Unit we will continue to help places develop localised approaches to climate change, housing and job creation. We will continue to argue for locally developed solutions and work to align national government investment with the priorities of local communities, and local impact. We will continue to codify what works and try to scale and spread the ‘boldest and best’ innovations while helping Whitehall learn the lessons needed to change whole systems.

So what happened to Islwyn HEAT?

In 1991 the HEAT scheme completed on time, well under budget and to a high quality standard. Some of its older ex miners decided to call it a day, some were retained by the Council in other roles and some went back to the job market with a new set of skills.

HEAT reduced fuel poverty (some tenants agreed to track their heating costs for a time) saved the council huge annual bills on property maintenance and enabled them to keep rent increases to an affordable minimum (from Peter Docherty).

HEAT was seen as best practice but the model did not become widespread (like so much ‘best practice’.) Some neighbouring local authorities in other parts of South Wales admitted they would struggle to adopt it. It was swimming against the tide of local government outsourcing, privatisation and retrenchment. In Islwyn’s case the maverick with the right political backing made the difference.

Huge thanks go to Mr Peter Docherty the iconoclastic maverick and giant of the UK housing sector. Peter can be found here.

What of the other characters? The Manic Street Preachers went on to become one of the biggest bands in the UK. Their album was released to much acclaim in 1998. They still knock out the odd tune.

Baron Neil Kinnock was MP for Islwyn until his retirement in 1995. He went on to become Vice President of the European Commission and serves in the House of Lords. Steve Strange died of a heart attack in 2015.

Finally, I would draw attention to the work of Professor Steve Fothergill of Sheffield Hallam University who has written extensively on the impact of the destruction of the mining industry on the communities it sat within.

Like any child of the coalfields, in retelling this story I am taken back to the mining memories in my family. My maternal grandfather David Edward James died in 1949 at the age 39 of pneumoconiosis, having mined since the age of 14. My paternal grandfather Caleb John Rees managed to reach 62 before dying in 1972 of the same illness. At least I was lucky to have known him. In small part I would like to dedicate this story to their memory.