Successful place-based transformation requires an inclusive strategy for local economic growth

blog | Words Mike Rees | 14 May 2021

The penultimate blog in our series on place-based transformation looks at why new approaches to local economic development are emerging. In particular we look at asking more serious questions about local impact.

Much of the current debate around the future of our national, post-Brexit economy resonates with phrases such as “left-behind towns” and “levelling up” between the north and south. This conversation is the latest iteration of a problem that has beset western economies over the last 30 or more years: rising rates of income inequality that have hit some places harder than others.

History has a long tail. Despite the collapse of traditional industries we still tend to associate certain places with certain industries – Hull with fishing, Glasgow with shipbuilding, Dagenham with car manufacturing and so on. As the Brexit result illustrated, identity and economy matter to people.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, places hit by industrial decline sought to reinvent themselves or “regenerate”. Some succeeded, such as cities like Manchester and Birmingham, which were able to grow on the back of retail, services and a huge expansion of higher education and migration.

Others did not. In response to this, Lisa Nandy MP for Wigan established the Centre for Towns think tank in 2019, campaigning for a pivot away from cities as the natural engines of economic growth.

In the course of trying to stimulate economic activity using a generic template, local authorities over the last 30 years have found the identity of towns – some of which were full of historic buildings – have changed. Many now look identical, with the same out-of-town retail and business parks, new housing developments and a web of link roads. Simultaneously, the family-run and independent stores located in traditional town centres have gone out of business.

This chiselling out of the notion of identity and place is thought by many to be a contributory factor in the Brexit debate. Even those places that thrived could still point to continued inequalities and plain old-fashioned poverty persisting in what might otherwise be considered a prospering and largely wealthy place.

New models

Many consider this version of economic development to have run its course and are turning to new models which recognise that many towns need a stimulus to meet their economic challenges but also that longer-term identity is central to future success – going with the grain of place so to speak.

One town that has shifted away from traditional thinking is Doncaster. Innovation Unit has worked with Doncaster Council for many years, specifically on its place-based approach to transforming support for adults experiencing severe and multiple disadvantage. We told the story of this work in our first blog in this series.

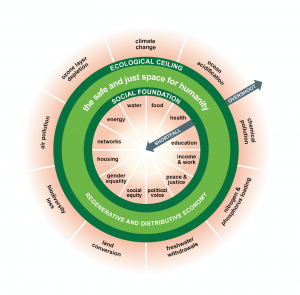

As part of its move to do things differently, Doncaster Council has embraced the notion of “doughnut economics”. This has been developed over the last decade by Professor Kate Raworth and advocates an ecological approach to developing economies that respect natural and societal boundaries.

Doncaster has sought to exemplify this approach with the support of local MP and Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Ed Miliband, in its strategy on climate and biodiversity emergency in 2020.

“Climate change matters because of the legacy we will leave to our children and grandchildren, but it also matters because we can create a much better economic future for people across our region by tackling it. Let’s talk about the dream, not just the nightmare. Imagine the cities and towns of the future: clean, green, with decent air quality, hospitable to walking and cycling, powered by renewables, with green space, not concrete jungles, and rewarding jobs in green industries – we already know that these things can happen, and are already beginning to happen around the world.”Ed Miliband MP

Travel west to Preston in Lancashire and there you will find local leaders who have been working hard to transform the local economy. When the 2008 financial crisis hit, the city town had already experienced several decades of industrial decline and economic restructuring, which had left it one of the most deprived parts of the country. After the crisis, its leaders focused on using the tools at their disposal to prevent wealth “leaking” out of Preston, and channelling key organisations to create local wealth that would have tangible benefits for residents and businesses in the city.

It embraced community wealth building and introduced a model of radical innovation in local government that uses mechanisms including anchor institutions, living wage expansion, community banking, public pension investment and worker ownership to achieve its aims.

The investment in ‘The Preston Model’ is paying off. In 2015, Preston was lifted out of the bottom 20 percent of the most deprived areas in England and by 2017 had improved its position from 143rd to 130th in the social mobility index (out of 324 local authority areas).

No more business as usual

In recent years, Wigan Council has become known for its ‘Wigan Deal’ approach. Innovation Unit has worked with Wigan over many years, from its Creative Councils project to transform adult social care, to the development of wider innovation in children’s services and much more.

While the Wigan Deal started as a new social contract between public services and citizens it has broadened this philosophy to examine how it might inform its approach to economic development.

Wigan Council has been working alongside the Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) to develop its community wealth building framework. The council, alongside its public sector partners, are adapting recruitment, tendering and skills policies to better support local people and businesses. It will also focus on the green economy and other growth sectors, while still supporting co-operatives, social enterprises and community schemes under the auspices of the Wigan Deal.

“People talk about getting back to business as usual. Well actually, when you think about it, do we want to get back to business as usual? Because business as usual in Wigan meant a low-wage economy with a third of jobs in the borough paying below the real living wage.”Cllr Keith Cunliffe

Deputy Leader of Wigan Council

So, in three historic towns of northern England we are witnessing a fundamental rethink about what we mean when we say economic development, what a new economy might look like and a rediscovery of what this means for the notion of place and identity.

Innovation Unit is not an expert in local economic development – and from our work to transform public services, we understand keenly the negative impact of its absence. We are inspired by the pioneers grounding economic strategy in local identity and a resident-led vision for the future and are keen to partner with experts in this space.