What the Voice teaches us about co-design

blog | Words Claire Dodd | 02 Oct 2023

As people who are tasked with facilitating consultation, codesign, and amplifying unheard voices, the Voice referendum is close to our heart. We’ve been contemplating the referendum alongside big reflections as an organisation about our place as non-Indigenous designers and facilitators in the work we do with First Nations communities across Australia and Tangata Whenua in New Zealand, and internationally.

One of our key principles that we adopt across all our work is listening to and amplifying the voices of people most impacted. It seems impossible, then, that we would ignore the call for a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Australian Constitution.

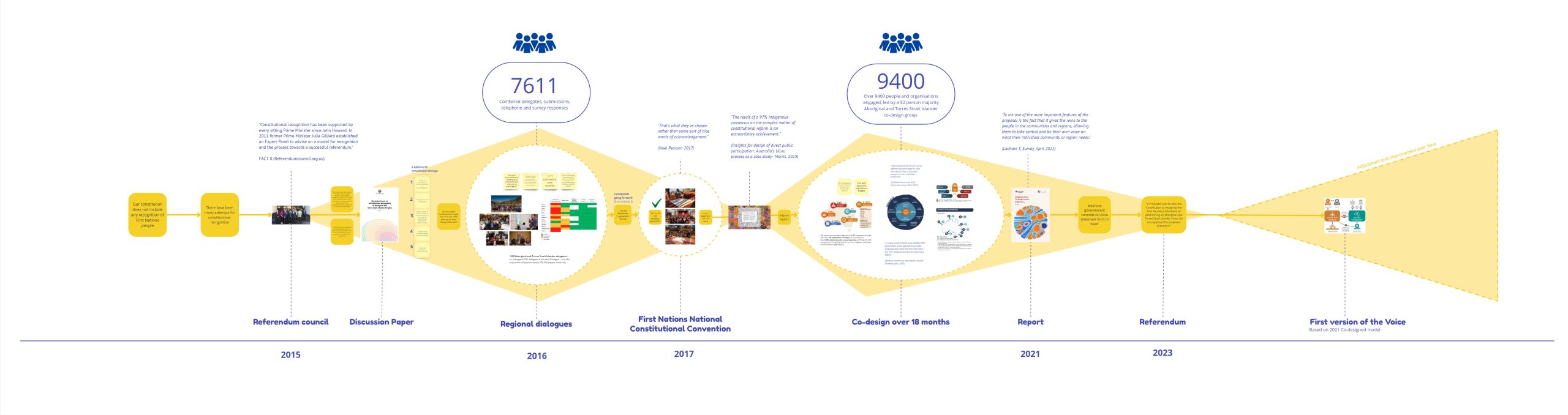

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice is the chosen way forward, decided by First Nations people. This didn’t come out of nowhere – it was the result of rich dialogue and co-design processes (more on that below) which built on many years of work, consultation, and previous proposals for constitutional change (and subsequent rejections or deferrals of those proposals). Five discrete options were presented to delegates of the dialogues and in the words of Noel Pearson:

“[The Voice] is what they’ve chosen rather than some sort of nice words of acknowledgement.”

– Noel Pearson 2017

The need for Constitutional recognition of this 65,000 years of continuous culture is almost universally agreed. When First Nations people were asked how this should happen, they resoundingly asked for more than symbolism. Responding to this call to establish something they decided they need, which in itself provides a continuing mechanism for their voices to be heard, just felt natural to support. However, being a group of curious people who like to understand what it is we are voting for, we embarked on learning more about this. What did we learn?

The consensus process that resulted in the Uluru Statement from the Heart and co-design process for the Voice are unprecedented and something from which we can learn so much. We pride ourselves on our capabilities to co-design with not for people, and supporting our project partners to do the same. But the depth and breadth of participation in the dialogue and co-design processes far surpasses that of most co-design or other participatory processes. Here’s what all co-design practitioners can learn:

Process led by First Nations people

Firstly, the dialogue process was First Nations-led. It wasn’t led by outside consultants or ‘experts’ to tell communities what they should do. The process itself was also co-designed by around 150 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditional owners, peak body representatives and individuals in 2016 and tested in a ‘test dialogue’ in November of that year.

Diversity of participants makes for stronger decision making

There was a large number and diversity of people involved in the dialogue process: 1,200 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across 13 locations (metro and regional). This represents the most proportionately significant consultation process that has ever been undertaken with First Peoples and it engaged a greater proportion of the relevant population than the constitutional convention debates of the 1800s.

Be active in seeking inclusion of often unheard voices

People did not come into the process by chance, and efforts were made to ensure inclusion of those typically excluded from consultation processes (e.g., travel for people located remotely and local language interpreting services). Up to 100 delegates were invited to each First Nations Regional dialogue, selected according to the following split: 60% of places for First Nations/traditional owner groups, 20% for community organisations and 20% for key individuals. At the end of each dialogue, all delegates were invited to nominate as delegates for the National Constitutional Convention at Uluru and these were voted in session.

Respect for the work and voices that have come before

The dialogues and the proposals for constitutional recognition didn’t come out of nowhere. They didn’t ignore or duplicate past work. They carried on a continuous line of work of the Referendum Council and many others in history who have worked persistently for First Nations rights (despite many obstacles) since the beginning of colonisation.

Provide the scaffolding for participants to understand what is being asked from them

People came into the process informed and had the chance to learn more in session about the proposals for constitutional recognition. Substantial time was allocated in each session for people to develop a deep understanding of why they were there, the history that led to the dialogues, what constitutional reform is, and what (in detail) are each of the reform options.

Move at the speed of relationships

The dialogue process wasn’t rushed. We know from experience that sufficient time is required to work through processes like this, to build a trusting space, for people to process information and ask questions, and for many different voices to be heard (really heard). Consultations took place across 13 locations (metro and regional) over 6 months. Each dialogue was held over two and a half days, beginning at 12.30pm on day 1 and ending with lunch on day 3.

Space for multiple stages of iteration

There were cycles of iteration of the dialogue outcomes. On the final day of each dialogue, for example, delegates were presented with a draft Record of Meeting which synthesised the discussion and debate from the plenary sessions and provided the opportunity to make changes.

Sharing the outcomes openly

Results of the process have been shared openly and widely. What happened and the outcomes of each dialogue were recorded and shared on the Referendum Council website very quickly following each meeting. The ‘Final Report of the Referendum Council’ (2017) was published soon after the conclusion of the dialogue process and includes the process in detail as well as the outcomes.

Deliver key principles as well as proposals

The process resulted in not only selected reforms – the ‘things’ that need to happen – but the guiding principles that should underpin any future actions. This means this extensive consensus process can have long-lasting impacts, as long as the principles are embedded in whatever changes or actions take place. The principles also provided a lens through which the reform options could be assessed (in addition to recognising which reforms were most popular).

Reaching a genuine consensus

The dialogue process genuinely resulted in clear decisions. A Voice to Parliament and Agreement-Making were endorsed and met all the guiding principles. Only a very small number of people who took part in the process were not in agreement with this outcome. This kind of consensus is rare. The Voice to Parliament was agreed as the first option to pursue, so that it might support and promote a treaty-making process.

“The result of a 97% Indigenous consensus on the complex matter of constitutional reform is an extraordinary achievement.”

(”Insights for design of direct public participation: Australia’s Uluru process as a case study”- Morris, 2019)

Designing the details with even greater participation

You would think that would be enough, but what came next was another highly participatory co-design process to design the details of an Indigenous Voice where the feedback overwhelmingly supported the need for an Indigenous Voice. A total of 9,478 Australians (about 95% of whom were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander) participated in this process through: 115 community consultation sessions in 67 locations, 2,978 submissions, 1,127 surveys, 124 stakeholder meetings, 1,486 participants in 13 webinars.

So, we got a bit excited about the details in the process. But, what does it really mean?

The Voice is what First Nations people have asked for. It won’t heal all past traumas and fix all our nation’s problems, but it is a step in the right direction (and the foundation upon which agreement-making can happen).

First Nations people are overrepresented in so many systems that we at IU work in regularly. When we encounter these systems, we hear they don’t work well for First Nations people (and often others too) and recognise there are often colonial mental models that continue to hold the systems in place. We also know from experience that the best chance we have at transforming these systems (or services, programs, etc.) is when people most impacted by them have their voices heard, or even better lead the change.

Sometimes this means that we need to get out of the way for others to lead. In this we want to amplify some of our friends and partners who do amazing work in ensuring that an Aboriginal perspective shines in both process and outcomes.

– Tash Kickett and Renee Ronan at Kaarla Baabpa

– Mandy Gadsdon at Think Culture

– Kyalie Moore at Boomerang Consultancy

– Jonathan and Danny Ford’s team at Kambarang Services

We at IU ANZ commit to listening to First Nations people and responding to their call to vote Yes on October 14th. We also commit to continue walking alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; listening and responding to what comes next.

Click here to see a visual representation of the consensus and co-design processes that led to the Voice created by Emma Whettingsteel.